With the recent FCC definition of broadband changing to 25/3 Mbps, the impact on DSL based Internet services could be significant. Since potentially millions of DSL lines in the U.S. aren’t capable of 25/3 Mbps, by one definition, they are no longer broadband. Does that mean DSL should be considered the new dial-up Internet? The answer is complicated.

With the recent FCC definition of broadband changing to 25/3 Mbps, the impact on DSL based Internet services could be significant. Since potentially millions of DSL lines in the U.S. aren’t capable of 25/3 Mbps, by one definition, they are no longer broadband. Does that mean DSL should be considered the new dial-up Internet? The answer is complicated.

DSL services that are not FTTN based like AT&T’s U-verse, are challenged to deliver broadband services that can provide 25/3 Mbps. These “challenged” DSL services are offered by virtually every telco (with the exception of a small minority who have completed total FTTP upgrades) in America from large carriers like Verizon, AT&T, CenturyLink and others, down to the smallest of rural telco or cooperative.

“Interestingly, I think 25/3 effectively takes DSL out of being classified as being broadband,” said Vermont Telecommunications Director Jim Porter in a recent interview.

Is DSL Now Relegated to Dial-Up Status?

Dial-up Internet was the first mass market approach to Internet access, utilizing PSTN phone lines, which topped out at 56 Kbps. As DSL and cable modem access (and to some extend fixed wireless services) became prevalent, dial-up was relegated to ‘second class’ status for Internet access. While their are a few laggards, dial-up is no longer considered a viable access medium to the Internet.

With the growing adoption of faster Internet connections and the recent FCC definition change, could we soon say the same about traditional DSL?

In some ways, the market is answering that question. While there is growing adoption of much faster Internet speeds (although the U.S. average is still 11.5 Mbps), thanks in large part to the growing Gigabit Internet phenomenon, there are still millions of traditional DSL customers – many of whom are satisfied with the speed they receive.

In a recent national survey, Telecompetitor and Pivot Group found that only 12% of current DSL subscribers indicated some frustration with their Internet speed (by indicating it was slow “usually or all of the time”) — not exactly an overwhelming referendum on dissatisfaction with DSL service.

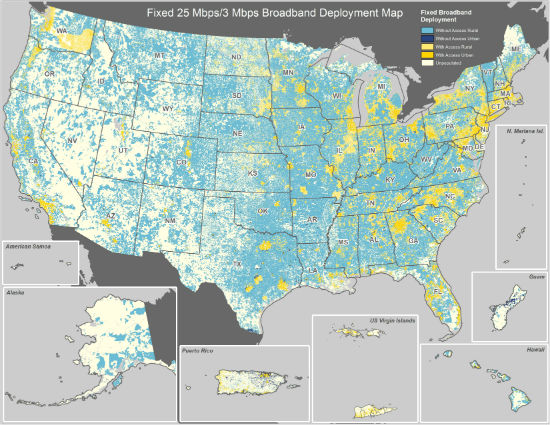

With regards to 25/3 Mbps broadband, FCC data says:

- 17 percent of all Americans (55 million people) lack access to 25 Mbps/3 Mbps service.

- 53 percent of rural Americans (22 million people) lack access to 25 Mbps/3 Mbps.

- 63 percent of Americans living on Tribal lands (2.5 million people) lack access to 25 Mbps/3 Mbps broadband

- Americans living in rural and urban areas adopt broadband at similar rates where 25 Mbps/ 3 Mbps service is available, 28 percent in rural areas and 30 percent in urban areas.

So according to FCC data, where 25/3 Mbps is available (the yellow shaded areas in the above map – the green/blue shaded area is where 25/3 Mbps is currently not available), roughly 30% of subscribers are adopting it. That’s a solid base, and no doubt, it’s growing. So while traditional DSL may not be relegated to dial-up just quite yet, the FCC’s heightened “bully pulpit” on faster broadband may push it in that direction, sooner, rather than later.

But Wait, Is it 25/3 Mbps or 10/1 Mbps?

Remember I said it’s complicated. In true FCC fashion, it appears they’re having it both ways. In reality, there are now two FCC definitions of broadband. If a carrier wants to qualify for Universal Service funds (USF), or Connect America funds (CAF), as USF is now becoming, 25/3 Mbps is not the standard. Rather 10/1 Mbps is.

The FCC has been adamant that they will not increase the USF fund under the new CAF auspices, which is supposed to fund broadband deployment in underserved and unserved markets. That fund currently stands at roughly $4.5 billion annually, and was historically used to bring phone service at affordable rates to everyone (although it has long funded broadband deployments in rural markets, even before the CAF).

Carriers serving rural America have long argued that is not enough funding to reach all unserved and underserved communities under the past 4/1 Mbps definition. To reach 10/1 Mbps with the same amount of funding would be impossible, they argue. To even suggest 25/3 as a target for CAF supported broadband is a stance even the FCC could not stomach.