As the FCC gets set to address inadequacies with the way broadband availability data is collected from service providers, USTelecom is warning that those efforts are only part of the solution to broadband mapping problems. To know which U.S. homes and businesses do not have broadband available to them, we also need to know the exact geographic coordinates of those homes and businesses. And perhaps surprisingly, that information doesn’t exist, explained Mike Saperstein, vice president of policy and advocacy for USTelecom, on a webcast today, in which the organization offered an update on the USTelecom broadband mapping initiative.

As the FCC gets set to address inadequacies with the way broadband availability data is collected from service providers, USTelecom is warning that those efforts are only part of the solution to broadband mapping problems. To know which U.S. homes and businesses do not have broadband available to them, we also need to know the exact geographic coordinates of those homes and businesses. And perhaps surprisingly, that information doesn’t exist, explained Mike Saperstein, vice president of policy and advocacy for USTelecom, on a webcast today, in which the organization offered an update on the USTelecom broadband mapping initiative.

“If we map only where broadband is, we have no idea where broadband isn’t,” Saperstein said. “We don’t know physically where the unserved locations are.”

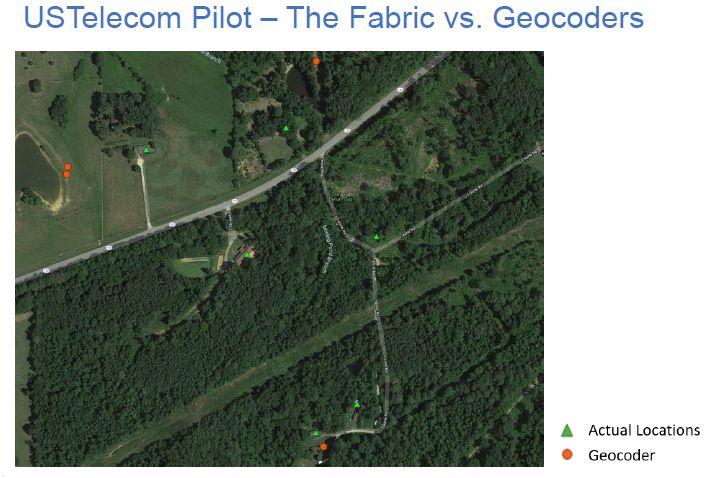

That’s important because service providers need to know the precise location within a farmer’s acreage of the family home to determine the cost to serve that home. But as slides shown during the webinar illustrate, geocoding systems often don’t show the correct location of rural homes within a farmer’s or rancher’s holdings.

The good news, Saperstein said, is that the USTelecom broadband mapping initiative suggests that solving that part of the problem “isn’t as hard as it seems.”

USTelecom Broadband Mapping Initiative

Broadband provider organization USTelecom launched its mapping initiative in March and has been working on creating what Jim Stegeman, president and CEO of CostQuest, called a proof-of-concept “broadband serviceable fabric” for Virginia and Missouri. CostQuest specializes in data about broadband deployments and was responsible for creating the cost model that underlies the FCC’s Connect America Fund. The company is also working with USTelecom on the broadband mapping initiative.

Also participating in the initiative are several other broadband organizations and broadband service providers, including AT&T, Verizon, CenturyLink, the Wireless Internet Service Providers Association, ITTA – The Voice of America’s Broadband Providers and others.

USTelecom, CostQuest and other participants followed several steps to create the broadband fabric, explained Stegeman. They began with data showing parcel boundaries (which, in general, depict the boundaries of a farmer’s or rancher’s holdings.) They augmented that data with information from tax assessors about how the land is used (commercial, agricultural, residential, etc.) and about primary and secondary structures on the land. They also brought in data showing building polygons – essentially a bird’s eye view showing the outer dimensions of every building on a farm, including garages, chicken coops and homes.

Current rules for broadband programs such as the Connect America Fund call for bringing service only to the primary location on an individual homestead (although that definition could broaden in the future). Accordingly, logic developed to analyze the data makes a determination about the location of the primary location on a property, and a specific confidence level is calculated for that determination. A designated team then reviews the data. The review process also could use crowd sourcing to hone the results, Stegemen noted.

USTelecom expects to submit full results from the pilot mapping initiatives in Virginia and Missouri to the FCC this summer and estimates that a fabric for the entire country could be created sometime in 2020. The FCC could then use the fabric in combination with shapefiles, also known as polygons, from service providers showing where the providers offer broadband to determine which U.S. locations do not have broadband available to them. Creating the nationwide fabric would cost between $10 million and $12 million by USTelecom’s estimate.

In an email response to an inquiry from Telecompetitor, a USTelecom spokesman said “We are funding the pilot as a proof of concept that the fabric can deliver a targeted view of broadband service availability. We have been keeping the FCC involved with our process and demonstrating our results to them; our hope is that they will adopt the fabric nationwide as part of their ongoing proceeding. To do so they will need to make provisions on their end (for example, a vendor that would produce the fabric.)”